By Dr Avnita Amin

Dr Avnita Amin, was a visiting researcher to the archives who accessed the Saunders collection earlier this year for her MPhil dissertation on the architectural design of St Christopher’s Hospice. She kindly agreed to write a shortened piece relating to her research for the blog.

The place of death remains a significant aspect of the process of dying and centres around the home, hospital and hospice. Dame Cicely Saunders (1918-2005) was widely recognised as the founder of the modern Hospice Movement after she instigated the building of St. Christopher’s Hospice in Sydenham, South East London.[1] She argued that hospice is a philosophy – a philosophy which “continue[s] to be concerned both with the sophisticated science of our treatments and with the art of our caring, bringing competence alongside compassion.”[2] It has been asserted that Saunders did not fully consider how the philosophy of hospice care she pioneered was underpinned by spatial practices[3] – yet an examination of the archival material reveals that, in fact, the geographical site and design of St. Christopher’s – the first modern hospice – was at the forefront of her mind. St. Christopher’s Hospice was designed to provide a physical space within which, for Saunders, a care based on love and devotion – with its historical religious underpinnings – could be combined with the most up-to-date medical advances in treatment. St. Christopher’s was to be a hybrid, specifically “planned as somewhere between a hospital and a home.”[4] St. Christopher’s was designed to continue the religious tradition of care and compassion whilst also providing facilities for up-to-date medical care and research. It was a unique building that created three main places – community, home and clinical.

The Need for a New Space

Since the nineteenth-century, hospitals were built to be highly functional and efficient spaces, allowing for classification of disease and the role of the bed changed from being a private place to one of increasingly professionalised investigation. This ‘clinical gaze’[5] required an increase in levels of hygiene, lighting and observation rather than the traditional notions of rest and comfort and resulted in the concomitant loss of patient dignity, privacy and individual status. The popular ‘Nightingale’ wards – long, open spaces with thirty beds arranged up and down the room became a standard ward layout of the late nineteenth century and continued to influence hospital design into the twentieth century. [6] Surveys were conducted across different hospitals to provide recommendations on design and layout of the hospital. Increased single-rooms and bathroom facilities were recommended, to facilitate some patient privacy but in the most part, to reduce infection rates, increase flexibility and efficiency of bed space utilisation, “albeit at the expense of nursing ease of patient supervision.”[7] In addition, clean and dirty spaces could be better separated and treatment areas could be completely removed from bed areas. Modernist hospital architecture sought to symbolise the modern medicine being practised within the building and focus was on clean lines and natural light through large windows. Hospital design could now offer medicine “an overwhelming improvement in efficiency”[8] and with the growing social and economic demands on the National Health Service, these large, efficient structures that concentrated specialist care to encourage greater throughput of patients, was welcomed. Smaller hospitals were closed down or moved to sites closer to the powerhouse teaching hospitals, which would serve “the whole country rather than just the area they were in.”[9] By the late 1950s and early 1960s, hospitals stood as powerful symbols of the curative powers of modern medicine, built to enhance efficiency and, arguably, resulted in the loss of patient dignity and person-centred care. Despite the goals of the new hospital buildings, continued use of older buildings led to provision of subpar care, in spite of skilled nursing. The buildings themselves were too outdated to fulfil the aims of the modern hospital.

Since the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century, hospitals also became spaces for the ‘medicalisation of death.’ Death had traditionally occurred in one’s home, surrounded by family and was a public affair. The sick who would previously have been too unwell to have treatment could now be treated in hospital with new technology and modern medicines that had the ability to treat a wider variety of diseases. Yet this enhanced the view that death in the hospital was a ‘failure’ of medicine. Patients were moved to a private, hidden, space and as death drew near, the medical team would remove itself for there was ‘nothing more to be done.’[10] As hospital planning texts of the 1950s indicate, there was little attention paid to providing specific spaces for the dying and if these were needed, ought to be positioned furthest from the nurses’ station and main ward, to avoid disturbing or depressing other patients.[11] With further technological advances in medicine came a belief that almost all disease could be cured and the dying became incorporated into this ethos of prolonging life.[12] Yet medicine is, arguably, not just an applied health science in the general pursuit of cure but also a moral enterprise and one which values the individual. The conflict between cure and care came to a fore in the 1950s with voices of discontent on care of the dying appearing in leading medical journals.[13] A new solution was needed – and Saunders’ identified the purpose-built hospice as the answer.

The Denmark Hill Site

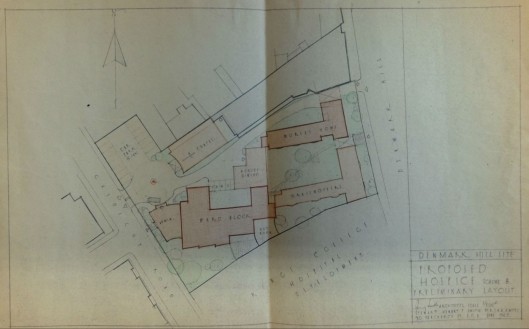

Fig. 1: Site plan for proposed hospice at Denmark Hill, 1962

“Whatever the type of space, it is through this engagement with, or being engaged by, particular spaces that their status shifts, they are transformed from mere physical areas into places through being endowed with meaning and significance.” (my italics)[14]

In describing her design for St. Christopher’s, Saunders weaved in observation and personal experience together with the envisaged functions of specific areas as well as the atmosphere she wished to create. By comparing the design description to actual experiences of the final spaces a clearer picture emerges of how successful the design of St. Christopher’s was in creating places of meaning for patients, relatives and others. Arguably, one of the most important aspects was the site and what has not been described before is that Saunders was actually offered a plot of land at Denmark Hill, initially planned for hospital development by King’s College Hospital, London. This site was acquired in 1904 and the new King’s College Hospital was opened in 1913. It joined the National Health Service in 1948, managed by a Board of Governors. During the 1960s, nearby Camberwell Hospitals were consolidated onto the Denmark Hill Site and a new Dental School and maternity block were added.[15]The cheaper site with its ability to share other financial burdens – such as kitchen costs – with the main hospital may have provided a shorter building time and less financial difficulties. Saunders contemplated the site and even had plans drawn up for the design. The site, however, was smaller than Saunders intended, and the close proximity to the Hospital would not have allowed for expansion. Saunders was adamant that the Hospice be outside the National Health Service, as it was a “pioneer project” with a religious foundation and must be free to remain so. Saunders felt that being in the literal shadow of the Hospital would only limit the flexibility and freedom which she envisioned for the Hospice. She herself recognised the need for physical distance from the local hospital, whilst still maintaining contact with it for teaching purposes and still appreciated the necessity of having contractual arrangements with the Health Service to ensure free care for the majority of patients.[16] Had Saunders accepted this site, her vision of a Hospice may have evolved quite differently. Building on the Denmark Hill site meant compromising on the size of the buildings and would have decreased the numbers of patients the hospice could care for and pushed treatment spaces, such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy, into underground spaces. It is interesting to note that at this time, whilst the new modernist approach of ‘form reflecting function’ was forming the basis for new hospitals within the National Health Service, restrictions of finance, the multiplicity of needs and limited physical space in urban areas led to continual setbacks in design, planning and building. [17] Saunders’ active choice to build the Hospice outside the bureaucracy and constrictions of the National Health Service allowed for a flexibility in design and building which were important in creating the philosophy of hospice care that evolved from St. Christopher’s and which, had the Hospice been built within the structure of the Health Service, would arguably have evolved differently.[18]

During her time at St. Joseph’s Hospice, Saunders worked in the new, purpose-built wing, designed by Peter Smith, architect at Stewart, Hendry and Smith. Opened in 1957, it supplied seventy-five beds to use for the terminally ill, freeing up the older buildings to house those with chronic conditions. It was during construction that Saunders and Smith met and when she began to plan St. Christopher’s Hospice, she contacted him to design the building. The design of both Our Lady’s Wing at St. Joseph’s and St. Christopher’s Hospice reflected a new architectural style of modernism which rejected excessive ornamentation but rather followed the idea that ‘form follows function’, resulting in designs that were intended to be harmonious with their intended purpose. Characteristics of this style were straight lines, geometric forms, metalwork and extensive use of glass and cantilevered elements, such as the indoor ‘balcony’ at St. Christopher’s. [19]

With an emphasis on comfort and homeliness, one may have expected Saunders to have leaned towards a more residential design for St. Christopher’s but her choice in architect Peter Smith’s plans for a modernist building arguably suited her vision to create a “new English Hospice” that combined an atmosphere of home with modern equipment and a new attitude and medical treatment method for pain relief.[20]

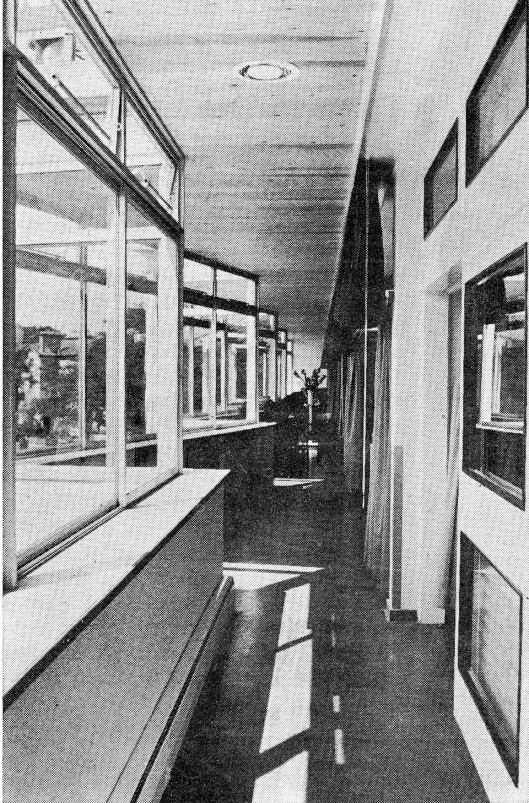

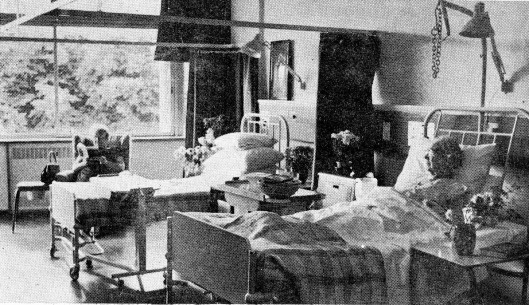

Saunders expanded on the basic design of Our Lady’s Wing and envisioned three terminal wards, a mixture of six and four-beds, providing a total of sixteen to twenty beds. In addition, there ought to be three single rooms to provide privacy and intimacy for those in the final stages of dying.[21] Saunders was even more specific – beds were to be placed sideways to maximise space and she emphasised the need for “a feeling of space on entering the ward.” A day room was important to encourage patient interaction, which should be “cosy”, perhaps with a fireplace. With her experience as a nurse Saunders was aware of the practical needs – cupboards along the passage would be useful and that the bathrooms needed to be bigger to “bring in beds”, as well as a shower. Emphasis was also on hygiene and cleanliness – hallmarks of modern medicine but also providing a direct contrast to the squalid conditions described in home death reports[22] – there was to be a sluice at each end of the ward for waste disposal. A nursing station which had a “good view” of all the patients was also necessary, but in contrast to the ‘clinical gaze’ in hospitals, Saunders was attempting to ensure that nursing needs could be easily identified and facilitated for all patients. This was again in contrast to the commonplace practice in hospitals of the dying being removed to ‘hidden’ corners of the ward.[23] Lighting was also considered[24]; practical needs dictated the use of fluorescent lighting in main areas, but attention was given to creating a more welcoming atmosphere – tungsten, which provided a warmer, incandescent light, was used for bedheads, in the Chapel and entrance hall.[25] Natural light filled the patient areas through the incorporation of a cantilevered space running the length of the building, providing a “projecting day space to the wards, angled to catch the early sun”[26] – a modernist architectural twist to Saunders’ request for a balcony. For privacy, the ‘balcony’ spaces could be curtained off from the ward. Figure 2 shows some of the curtained four-bed bays and single rooms coming off the enclosed balcony, whilst image 3 shows a four-bed bay. Note the bedside lamps, flowers on the table and the informal, mixed use of the light-filled space – a young visitor reads whilst a patient lies in her bed looking out of the windows. If this was the homely, comfortable environment that Saunders wished to create, then arguably, it was the building’s design that facilitated this.

Fig. 2: Cantilevered Day Space, St Christopher’s Hospice, Sydenham (1967) in St Christopher’s Hospice. Nursing Times. 28th July 1967

Fig. 3. Four-bed ward at St Christopher’s Hospice, Sydenham (1967) in St Christopher’s Hospice. Nursing Times. 28th July 1967.

As a building can allow one to shelter in space, it can also allow one to shelter in time.[27] In stark contrast to the bleak spaces of contemporary hospitals, St. Christopher’s provided “warmth and welcome” and above all, time in the form of beds “without invisible parking meters”.[28] In the article celebrating the opening of this new hospice, the subtitle is ‘Time to Die’ and it is the atmosphere of “leisurely time”; time to talk, carry out nursing tasks unhurriedly and time for the patient to exercise independence, that is emphasised.[29] Saunders wanted to alleviate the crisis of the last stages of life, for this to be a “time of real living, held in the context of the life that both reaches beyond and envelops the everyday world.”[30] The purpose-built hospice sought to change the experience of the time close to death – “distress, fear and loneliness will disappear” and a time that can be “so hard or so dreary” would be transformed into one of “peace, security and meaning, a sort of homecoming.”[31] Time was given for patients to explore their own feelings through various methods – talking to staff, the Chaplain and even through creative means, such as poetry.[32]

For Saunders, the importance of St. Christopher’s as both a spiritual and medical endeavour became solidified as she developed the design and plan of the hospice. In the brochure, a specific section is dedicated to emphasising the modern scientific medicine that will be practiced, and improved, at St. Christopher’s.[33] This brochure was used to raise funds and it argued that the coupling of medical with general care made St. Christopher’s a unique enterprise worthy of establishment. As outlined in The Need, research into pain and other symptoms specific to the terminally ill was to be an important aspect of the work conducted at St. Christopher’s Hospice. To this end, Saunders specifically incorporated a post-mortem room and wrote to the Borough Coroner to ascertain any special requirements he might have.[34] Understandably, the room was not an aspect publicised in the brochure or public appeals.[35] It was built out-of-sight, under the access road to the site. By including this room, Cicely provided the space to conduct evidence-based research – important for a fledgling medical field to gain acceptance and authority in its treatments from medical colleagues and others.[36] Symptom-specific post-mortem studies were conducted after gaining explicit permission from family members and the results provided new insight into the causes of pain in the dying. These studies showed that pain described by patients could be due to more than just the primary cancer – in contrast to what was widely believed – and that pain control should be based on careful assessment of pain to identify the most appropriate medical treatment, be it further surgery or medication.[37] This work was further explored by Dr. Robert Twycross[38] who conducted clinical research into pain at St. Christopher’s in the 1970s. The Hospice provided a ready subset of patients for clinical trials, whilst the high standards of the purpose-built facility– matching those of the National Health Service – arguably added credence to any data that was published from the Hospice.

Impact Beyond St. Christopher’s

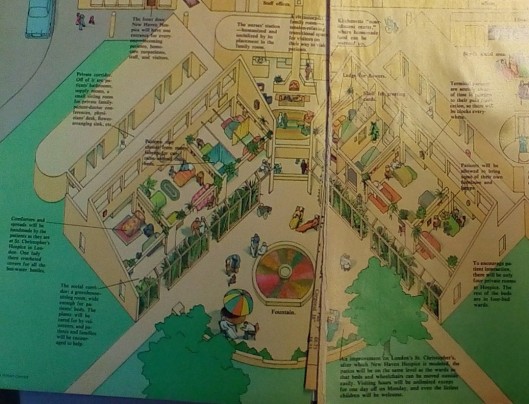

Not only did St. Christopher’s influence the building of hospices across Britain but it became the model for the first hospice in the United States – see Figure 4.[39] Architect Lo-Yi Chan was chosen from a number of entrants to design the New Haven Hospice – he stood out because he wished to visit St. Christopher’s should he win the assignment. During his visit he spoke to patients at St. Christopher’s and witnessed first-hand the community and compassionate atmosphere that underpinned the hospice philosophy. He came away from St. Christopher’s wanting to create an “architecture of healing” to provide a “therapeutic environment based on the patient’s point of view” – just as Saunders had emphasised multiple times.

From the beginning, Saunders identified St. Christopher’s as a building which would provide a sense of comfort, specialised care and up-to-date medical treatment for the specific needs of the dying. By focusing on the design of St. Christopher’s in more detail than has been previously done, it is argued that the philosophy of hospice care that was developed in St. Christopher’s had a specific spatial underpinning. This was in no small part due to Saunders herself, who envisioned in great detail and with great accuracy the final building and its wards, the bed layout, the need for flexible spaces to encourage both interaction and privacy. Architect Peter Smith provided a modernist interpretation of her ideas, a notable example of being the cantilevered day space with curtains which could provide a walkway of open space, or separate wards and rooms for privacy. St. Christopher’s truly was a hybrid building between a home and hospital – it succeeded in providing a domestic environment to create a sense of community and individuality whilst also maintaining a strong association with the tenets of research found in modern scientific medicine. The lasting impact of St. Christopher’s lies, not on its building design, which had minimal architectural value, but on the place created, the atmosphere it fostered and the sense of community. This was a community of the staff, linked with a community of the patients (who also provided support for each other) and spreading wider into the local neighbourhood – links with teaching hospitals to spread the hospice philosophy.

So, can a building make a difference? For Saunders it was a necessary part of the hospice philosophy:

Yes, of course, a building can help…A good building can make a difference to the backs and feet of the staff and to the patients’ spirits. Beauty is very healing. It makes patients see that the creation to which they also belong is good – it can be trusted.[40]

Fig. 4: “Designing a better place to die”, New York, (1978): 43-49

References:

[1] Lewis, Medicine, 6-11; The term ‘modern’ has been applied to this particular hospice movement to discuss the worldwide changes to care of the dying and proliferation of hospices from the 1970s onwards. As far as the author can tell, this term was not instigated by Saunders herself, but rather applied retrospectively.

[2] Cicely Saunders, Dorothy H. Summers, and Neville Teller. Hospice: The Living Idea (London: Edward Arnold, 1981), p4.

[3] McGann, Production, p5.

[4] Cicely Saunders. “St. Christopher’s Hospice.” In Transcript of speech given at the completion of building work, London, 1966. Box 7. Progress Reports: 1963-66. 1/2/10. King’s College London Archives.

[5] Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic (Abingdon: Routledge, 1973), xv.

[6] Thompson,J. and Goldin,G, The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (Yale: Yale University Press, 1975), 30

[7] Ibid, 29-31

[8] RIBA Joint Committee on the Orientation of Buildings, “The orientation of buildings” (London:RIBA, 1933), 3.; Hughes, “Matchbox”, 28.

[9] “The Cabinet Papers – Origins of the NHS,” last modified March 19, 2012, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinetpapers/alevelstudies/origins-nhs.htm.

[10] Philippe Aries, The Hour of Our Death: The Classic History of Western Attitudes Towards Death over the Last One Thousand Year, trans. H. Weaver (New York: Knopf, 1981), 560-571.

[11] McGann, Production, 19. Discussing “Charles, Butler and Addison Erdman. Hospital Planning (New York: F. W. Dodge corporation, 1946), 154”.

[12] Lewis, Medicine, 79.

[13] Lewis, Medicine, 124-125.

[14] Maddrell and Sidaway, Deathscapes, 3.

[15] “A history of King’s – King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust,” last modified June 26, 2014 https://www.kch.nhs.uk/centenary/a-history-of-kings.

[16] Ibid., 3.

[17] Hughes, “Matchbox”, 21-51.

[18] Du Boulay 200-226. The hospice philosophy developed at St. Christopher’s spread across Britain, worldwide and resulted in the transfer of this philosophy of care of the dying to four new spaces – the inpatient hospice unit, the special terminal care ward in a hospital, home care and the hospital support team.

[19] Ken Worpole, Modern Hospice Design:, 7 and Verdeber Refuerzo, Innovations in Hospice Architecture, 29

[20] Smith, Peter. “A New English Hospice”. [Report ], Box 7. Progress reports: 1963-66. 1/2/10. London: King’s London Archives.

[21] Saunders, Hospice: The Living Idea, 45

[22] See cit 26

[23] See cit 27

[24] Saunders, Cicely. “Letter to Smith”. [Letter], Box 7. 1/2/4. London: King’s London Archives.Saunders wanted to have a “nice diffuse light”.

[25] Smith, P.A New English Hospice. and Hughes, “Matchbox”, 32. – The Hospice design eschewed the contemporary trend towards artificial light and mechanical ventilation in the newly-designed Health Service hospitals.

[26] Smith. A New English Hospice. 4

[27] Ken Worpole, Modern Hospice Design: The Architecture of Palliative Care (New York: Routledge, 2009), p264.

Worpole. Modern Hospice Design. Kindle Edition. Location 264.

[28] Cicely Saunders. “St. Christopher’s Hospice.” In Transcript of speech given at the completion of building work, London, 1966. Box 7. Progress Reports: 1963-66. 1/2/10. King’s College London Archives.

[29] Cicely Saunders “St Christopher’s Hospice,” Nursing Times 28 July 1967: 1.

[30] Cicely Saunders. “St. Christopher’s Hospice.” In Transcript of speech given at the completion of building work, London, 1966. Box 7. Progress Reports: 1963-66. 1/2/10. King’s College London Archives.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Sidney Reeman, “Declaration of Dependence,” in St. Christopher’s In Celebration: Twenty-one years at Britain’s first modern hospice, ed. Cicely Saunders (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988), 58-62..

[33] St. Christopher’s Hospice. “St. Christopher’s Hospice brochure”. Annual Reports 1/2/31. King’s College London Archives.

[34]Saunders, Cicely. “Letter to the Coroner’s Office”. [Letter], Box 7. 1/2/92. London: King’s College London Archives.

[35] St. Christopher’s Hospice. St. Christopher’s Hospice (brochure). 1966.

[36] Overy and Tansey, Palliative Medicine, 38-40. The medical field that arose out of the hospice movement is now known as Palliative Medicine.

[37] R. L. Carter, “The role of limited symptom-directed autopsies in terminal malignant disease,” Palliative medicine 1 (1987): 31-36.

[38] Clark, David, “The rise and demise of the ‘Brompton cocktail’,” in Opoids and pain relief: a historical perspective. Progress in Pain Research and Management, Vol. 25, ed. M. L. Meldrum, (Seattle: IASP Press), 85-98. Dr Robert Twycross joined St. Christopher’s as a Clinical Research Fellow in 1968.

[39] Kron, J, “Designing a better place to die,” New York, (1978) : 43-49

[40] Kron, J. “Designing a better place to die,” New York, (1978) : 49